Original source

brianmichaelbendis:

大友克洋 AKIRA by Otomo

Nothing to see here.

Original source

brianmichaelbendis:

大友克洋 AKIRA by Otomo

Original source

McDonnell F3H-2M Demons. “McDonnell F3H-2M “Demons” of FS (VF) 61 launch simultaneously from the USS SARATOGA (CVA-60) during flight operations off Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, May 16, 1957.”

Original source nk497 writes “Police in Manchester have arrested a man and seized what they claim are 3D printed components to a gun. They made the arrest after a ‘significant’ discovery of a 3D printed ‘trigger’ and ‘magazine,’ saying they were now testing the parts to see if they were viable. 3D printing experts, however, said the objects were actually spare parts for the printer. ‘As soon as I saw the picture… I instantly thought, “I know that part,”‘ said Scott Crawford, head of 3D printing firm Revolv3D. ‘They designed an upgrade for the printer soon after it was launched, and most people will have downloaded and upgraded this part within their printer. It basically pulls the plastic filament, and it used to jam an awful lot. The new system that they’ve put out, which includes that little lever that they’re claiming is the trigger, is most definitely the same part.'”

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Original source

KentuckyFC writes “One of the great challenges in physics is to unite the theories of quantum mechanics and general relativity. But all attempts to do this all run into the famous ‘problem of time’

— &mdash — the resulting equations describe a static universe in which nothing ever happens. In 1983, theoreticians showed how this could be solved if time is an emergent phenomenon based on entanglement, the phenomenon in which two quantum particles share the same existence. An external, god-like observer always sees no difference between these particles compared to an external objective clock. But an observer who measures one of the pair — and so becomes entangled with it–can immediately see how it evolves differently from its partner. So from the outside the universe appears static and unchanging, while objects that are entangled within it experience the maelstrom of change. Now quantum physicists have performed the first experimental test of this idea by measuring the evolution of a pair of entangled photons in two different ways. An external god-like observer sees no difference while an observer who measures one particle and becomes entangled with it does see the change. In other words, the experiment shows how time is an emergent phenomenon based on entanglement, in which case the contradiction between quantum mechanics and general relativity seems to melt away.”

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

radiantbutterfly:Schrodinger’s Douchebag: One who makes douchebag statements, particularly sexist, racist or otherwise bigoted ones, then decides whether they were “just joking” or dead serious based on whether other people in the group approve or not.MOVING THIS INTO CIRCULATION IMMEDIATELY.

If an asteroid was very small but supermassive, could you really live on it like the Little Prince?

Samantha Harper

Last week, we looked at at life on a giant world. This week, let’s look at a small one.

The Little Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, is a story about a traveler from a distant asteroid. It’s simple and sad and poignant and memorable.[1] For another take on the Petit Prince, scroll down to the last section of this wonderful piece by Mallory Ortberg. It’s ostensibly a children’s book, but it’s hard to pin down who the intended audience is. In any case, it certainly has found an audience; it’s among the best-selling books in history.

It was written in 1942. That’s an interesting time to write about asteroids, because in 1942 we didn’t actually know what asteroids looked like. Even in our best telescopes, the largest asteroids were only visible as points of light. In fact, that’s where their name comes from—the word asteroid means “star-like.”

We got our first confirmation of what asteroids looked like in 1971, when Mariner 9 visited Mars and snapped pictures of Phobos and Deimos.[2] Here’s a picture of Phobos looking like the archetypical asteroid. The archived images from the mission are at the NASA Space Science Data Center, but strangely, the NSSDC refers readers to someone’s personal Tripod page to browse the actual images. These moons, believed to be captured asteroids,[3] Ironically, while Phobos and Deimos look like asteroids, new research suggests they’re not. See Craddock, Robert A.. “Are Phobos And Deimos The Result Of A Giant Impact?“. Icarus (2010) solidified the modern image of asteroids as cratered potatoes.

Before the 1970s, it was common for science fiction to assume small asteroids would be round, like planets.[4] Not always; plenty of people had a good idea of what they would look like. And there were stranger ideas …

The Little Prince took this a step further, imagining an asteroid as a tiny planet with gravity, air, and a rose. There’s no point in trying to critique the science here, because (1) it’s not a story about asteroids, and (2) it opens with a parable about how foolish adults are for looking at everything too literally.

So rather than trying to take things away from the story, let’s see what strange new pieces science can add. If there really were a superdense asteroid with enough surface gravity to walk around on, it would have some pretty surprising properties.

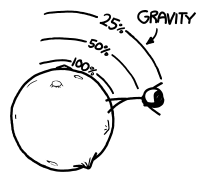

If the asteroid has a radius of 1.75 meters, then in order to have Earth-like gravity at the surface, it would need to have a mass of about 500 million tons. This is roughly equal to the combined mass of every human on Earth.

If you stood on the surface, you’d experience tidal forces. Your feet would feel heavier than your head, which you’d feel as a gentle stretching sensation. It would feel like you were stretched out on a curved rubber ball, or were lying on a merry-go-round with your head near the center.

The escape velocity [5]

… which is why it should really be called “escape speed”—the fact that it has no direction (which is the distinction between “speed” and “velocity”) is actually very significant here. at the surface would be about 5 meters per second. That’s slower than a sprint, but still pretty fast. As a rule of thumb, if you can’t dunk a basketball, you wouldn’t be able to escape by jumping straight up.

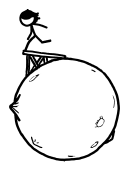

However, the weird thing about escape velocity is that it doesn’t matter which direction you’re going. [5] … which is why it should really be called “escape speed”—the fact that it has no direction (which is the distinction between “speed” and “velocity”) is actually very significant here. If you go faster than the escape speed, as long as you don’t actually go toward the planet, you’ll escape. That means you might be able to leave our asteroid by running horizontally and jumping off the end of a ramp.

If you didn’t go fast enough to escape the planet, you’d go into orbit around it. Your orbital speed would be roughly 3 meters per second, which is a typical jogging speed.

But this would be a weird orbit.

Tidal forces would act on you in several ways. If you reach your arm down toward the planet, it would be pulled much harder than the rest of you. And if you reach down with one arm, the rest of you gets pushed upward, which means other parts of your body feel even less gravity. Effectively, every part of your body would be trying to go in a different orbit.

A large orbiting object under these kinds of tidal forces—say, a moon—will generally break apart into rings. This wouldn’t happen to you. However, your orbit would become chaotic and unstable.

These types of orbits were investigated in an interesting paper by Radu D. Rugescu and Daniele Mortari.[6] Rugescu, Radu D., Mortari, Daniele, “Ultra Long Orbital Tethers Behave Highly Non-Keplerian and Unstable“, WSEAS Transactions on Mathematics, Vol. 7, No. 3, March 2008, pp. 87-94. Their simulations showed that large, elongated objects follow strange patterns around their central bodies. Even their centers of mass don’t move in the traditional ellipses; some adopt pentagonal orbits, while others spin chaotically and crash into the planet.

This type of analysis could actually have practical applications. There have been various proposals over the years to use long, whirling tethers to move cargo in and out of gravity wells—a sort of free-floating space elevator. Such tethers could transport cargo to and from the surface of the Moon, or to pick up spacecraft from the edge of the Earth’s atmosphere. The inherent instability of many tether orbits poses an interesting challenge for this kind of project.

As for the residents of our superdense asteroid, they’d have to be careful; if they ran too fast, they’d be in serious danger of going into a tumble and losing their lunch.

Fortunately, vertical jumps would be fine.