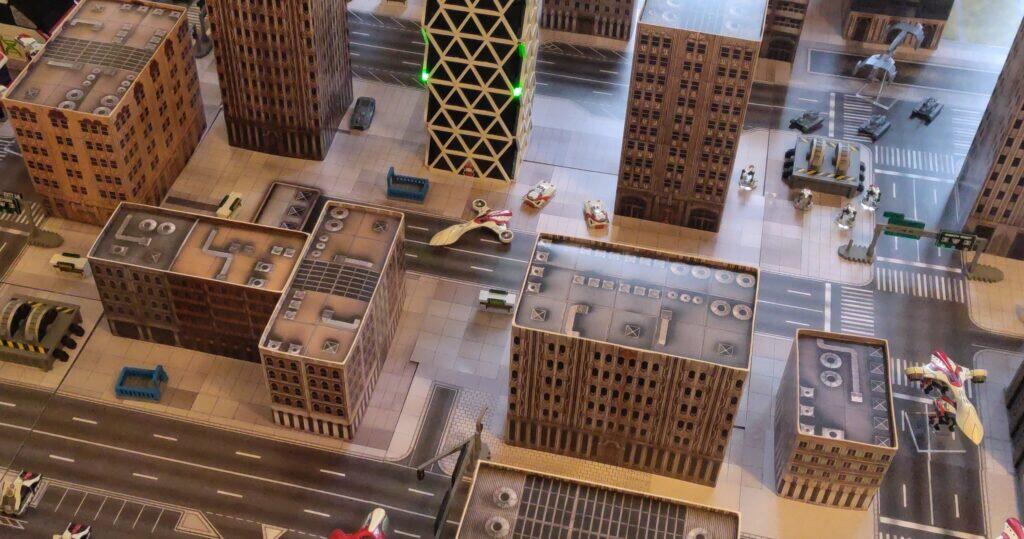

Moebius, Paradiso.

Nothing to see here.

Moebius, Paradiso.

Moebius, Paradiso.

Original source itwbennett writes “Broadcom Chairman and CTO Henry Samueli has some bad news for you: Moore’s Law isn’t making chips cheaper anymore because it now requires complicated manufacturing techniques that are so expensive they cancel out the cost savings. Instead of getting more speed, less power consumption and lower cost with each generation, chip makers now have to choose two out of three, Samueli said. He pointed to new techniques such as High-K Metal Gate and FinFET, which have been used in recent years to achieve new so-called process nodes. The most advanced process node on the market, defined by the size of the features on a chip, is due to reach 14 nanometers next year. At levels like that, chip makers need more than traditional manufacturing techniques to achieve the high density, Samueli said. The more dense chips get, the more expensive it will be to make them, he said.”

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Original source Hugh Pickens DOT Com writes “The Washington Post reports that the carjackers who set off international alarm bells by absconding with a truckload of highly radioactive cobalt-60, used in hospital radiotherapy machines, most likely had no idea what they were stealing and will die soon from exposure. The robbery occurred as the cobalt-60 was being driven from a public hospital in the border town of Tijuana to a storage facility in central Mexico. While waiting for daybreak at a gas station in the state of Hidalgo the drivers were jumped by two gunmen who beat them and stole the truck. “I believe, definitely, that the thieves did not know what they had; they were interested in the crane, in the vehicle,” says Mardonio Jimenez, a physicist with Mexico’s nuclear safety commission. The prospect that material that could be used in a radioactive dirty bomb had gone missing sparked an urgent two-day hunt that concluded when the material, cobalt-60, used in hospital radiotherapy machines, was found along with the stolen Volkswagen truck. The cobalt-60 was found, removed from its casing, in a rural area near the town of Hueypoxtla about 25 miles from where the truck was stolen. Jimenez suspects that curiosity got the better of the thieves and they opened the box. So far the carjackers have not been arrested, but authorities expect they will not live long. “The people who handled it will have severe problems with radiation. They will, without a doubt, die.””

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Giro director Michele Acquarone said Danilo Di Luca’s EPO positive is a sign of addiction. Photo: David Hecker | AFP

Giro director Michele Acquarone said Danilo Di Luca’s EPO positive is a sign of addiction. Photo: David Hecker | AFPROME (AFP) – The Italian Olympic Committee (CONI) banned Italian cyclist Danilo Di Luca for life on Thursday due to a positive test for the banned blood booster erythropoietin (EPO).

Di Luca tested positive for EPO in an out of competition test on April 29, forcing him to quit the Giro d’Italia.

Di Luca, 37, won the Giro in 2007, and finished second overall in 2009. He also served suspensions during both of those seasons — in 2007, for prior involvement with Italian doping doctor Carlo Santuccione, and in 2009, when he tested positive for using the blood-booster CERA during that year’s Giro.

Di Luca also delivered a urine sample during his 2007 Giro victory that reportedly recorded the hormone levels of a small child, dubbed “pipi degli angeli” (angel’s pee), a sign of the use of masking agents. However he ultimately was cleared for that offense, with CONI anti-doping officials admitting there was “not a sufficient degree of probability” for a doping conviction. He was able to keep his 2007 Giro title, though he was stripped of his 2009 second-place finish.

“He punched the Giro d’Italia in the stomach in 2007 and almost did it again in 2009,” former Giro d’Italia race director Angelo Zomegnan famously said on Italian television.

After serving a suspension, Di Luca returned in 2011 with Katusha, riding for no salary. He rode last year with Acqua & Sapone, and only opened his 2013 campaign after signing with Vini Fantini in late April. Shortly thereafter, he failed his out-of-competition drug test. Former Giro d’Italia race director Michele Acquarone called Di Luca’s 2013 positive test a “sign of addiction.”

As well as the life ban, Di Luca was also fined 35,000 euros, and his results since mid-April have been erased from the record books.

The post Danilo Di Luca banned for life after EPO positive appeared first on VeloNews.com.

One of the Carlson family’s favourite stock stories involved our first-ever ‘vacation’, in 1962, when the we went on a trek through Washington DC; Williamsburg Virginia; Bristol, Tennessee;

One of the Carlson family’s favourite stock stories involved our first-ever ‘vacation’, in 1962, when the we went on a trek through Washington DC; Williamsburg Virginia; Bristol, Tennessee;  I mention this because it is the sesquicentennial anniversary today of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, originally delivered at the dedication of the cemetery

I mention this because it is the sesquicentennial anniversary today of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, originally delivered at the dedication of the cemetery Pickett’s Charge, something of a misnomer because General George Pickett did not actually charge with his command, signifies what is recalled as the ‘high-water mark’ of the Confederacy. Faulkner wrote famously in

Intruder In The Dust of the way that ‘For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out.’ By the end of the afternoon, Robert E Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia will have, for the first time, been defeated; the next day, Vicksburg would fall to Ulysses Grant. But for a few hundred thousand more bodies, the Civil War was over.

For the Union,

For the Union, and treated him on the battlefield, became, as Stewart says, ‘a storm-centre of controversy’: ‘Say to General Hancock for me, that I have done him, and you all, a grievous injury, which I shall always regret’. Was he apologising for breaking his oath to serve the United States, or was it a more personal apology for perhaps under-estimating Hancock’s troops?

and treated him on the battlefield, became, as Stewart says, ‘a storm-centre of controversy’: ‘Say to General Hancock for me, that I have done him, and you all, a grievous injury, which I shall always regret’. Was he apologising for breaking his oath to serve the United States, or was it a more personal apology for perhaps under-estimating Hancock’s troops?  but he was removed from command, and from Lee’s sight. Pickett, with his long ringlets and sharp angled face, reminds us of two other American heroes, Poe (like the author, Pickett courted, and married, a teenaged girl) and Custer, as flamboyant and also foolhardy.

but he was removed from command, and from Lee’s sight. Pickett, with his long ringlets and sharp angled face, reminds us of two other American heroes, Poe (like the author, Pickett courted, and married, a teenaged girl) and Custer, as flamboyant and also foolhardy. The Gettysburg Address remains the single most powerful speech in American history, and a model of concision for the world. The people who came to Gettysburg for the dedication ceremony might well have come to hear Edward Everett, a renowned orator, and he gave them their money’s worth, speaking for two hours. Everett later wrote to Lincoln, requesting a copy of his speech, saying Lincoln had said better in two minutes what had took him two hours. The Everett copy is one of the five known to exist. Garry Wills’ Lincoln At Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America (1992) is a fine exegesis of the speech itself, and its effect: it is a commonplace now to note that before the Civil War, United States was not a collective noun in the American sense; it still took a plural verb. After the Civil War, it became a collective, requiring the single verb a united group deserves. That was down to Lincoln, but at Gettysburg he made a simple declaration—we, the people, could not consecrate the battle ground, the dead and living who fought there had already done that. We who did not fight there could only apply ‘increased devotion’ and ‘highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom’. In many ways today, his words, stirring as they are, ring hollow even as they are recalled and intoned, because we are still waiting.Both sides of America must endure their own legacies of failure.

The Gettysburg Address remains the single most powerful speech in American history, and a model of concision for the world. The people who came to Gettysburg for the dedication ceremony might well have come to hear Edward Everett, a renowned orator, and he gave them their money’s worth, speaking for two hours. Everett later wrote to Lincoln, requesting a copy of his speech, saying Lincoln had said better in two minutes what had took him two hours. The Everett copy is one of the five known to exist. Garry Wills’ Lincoln At Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America (1992) is a fine exegesis of the speech itself, and its effect: it is a commonplace now to note that before the Civil War, United States was not a collective noun in the American sense; it still took a plural verb. After the Civil War, it became a collective, requiring the single verb a united group deserves. That was down to Lincoln, but at Gettysburg he made a simple declaration—we, the people, could not consecrate the battle ground, the dead and living who fought there had already done that. We who did not fight there could only apply ‘increased devotion’ and ‘highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom’. In many ways today, his words, stirring as they are, ring hollow even as they are recalled and intoned, because we are still waiting.Both sides of America must endure their own legacies of failure.Original source Hugh Pickens DOT Com writes “The Telegraph reports that NASA plans to send turnip, cress, and basil seeds to the Moon inside a specially constructed canister, known as the Lunar Plant Growth Chamber. The chamber will carry enough air for 10 days and NASA says the air in the chamber would be adequate to allow the seeds to sprout and grow for five days. It is hoped that the latest experiment will help to pave the way for astronauts to grow their own food while living on a lunar base. NASA says it will use natural sunlight to germinate the plants inside the chamber and the seeds will grow on pieces of filter paper laden with nutrients. ‘If we send plants and they thrive, then we probably can. Thriving plants are needed for life support — food, air, water — for colonists. And plants provide psychological comfort, as the popularity of the greenhouses in Antarctica and on the Space Station show.’ The Lunar Plant Growth Chamber is expected to weigh around 2.2lbs and will also carry 10 seeds each of basil and turnips. Upon landing on the Moon a trigger would release a small reservoir of water to wet the filter paper and initiate the germination of the seeds. Photographs of the seedlings would be taken at regular intervals to monitor their progress and compare them to seedlings being growing in similar conditions on Earth.”

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

On Public Enemy’s Fear Of A Black Planet, there’s a track called “Incident At 66.6 FM” – a 90-second cut-up of derisive, racist radio commentary on the band that brings you-the-listener right up to speed on why they felt besieged, and puts you on their side for the fightback. The first thirty seconds of “Three Lions” pull off a very similar trick for a rather less radical cause: England fans. It’s

On Public Enemy’s Fear Of A Black Planet, there’s a track called “Incident At 66.6 FM” – a 90-second cut-up of derisive, racist radio commentary on the band that brings you-the-listener right up to speed on why they felt besieged, and puts you on their side for the fightback. The first thirty seconds of “Three Lions” pull off a very similar trick for a rather less radical cause: England fans. It’s with a compact, adroit bit of pop scene-setting. In the background, the low swell of a stadium rousing itself for battle. In the foreground, critics officiate at a funeral. “I think it’s BAD NEWS for the English game…not CREATIVE enough, not POSITIVE enough… we’ll GO ON getting bad results…”

Wait, though – even as these suited carrion birds gather, we hear another voice – lone and thin, but firm and honest, singing a song that is halfway to a prayer. “It’s coming home, it’s coming home… “ Against the ranks of pessimism, cynicism, analysis and fact, against their own better judgement, the fan can’t help but believe. Football is coming home.

It’s a magnificent bit of manipulation: the marketer in me swoons in admiration. The rest of “Three Lions” develops the theme but all you need to know is in that intro. Who, on hearing it, wouldn’t be on the side of the fan’s simple faith against the doomsayers? In half a minute “Three Lions” defined the English game’s sense of itself for the rest of the 90s, and the 00s too – sentimental belief against obstinate fact, with the former winning the moral victory every time.

Like all football number ones, “Three Lions” is an artefact from a changing game. Plenty of middle-class Brits had always liked football, but Italia 90 had cemented that audience as the game’s great new revenue stream, World Cup-weaned fans who liked heartbreak and tears and big stories with regular helpings of ‘glory’ and ‘passion’. At the club level this breakthrough demographic were well-served by Man United’s ascendancy and the Premier League’s early boom – but at an international level the development had been held back by the woeful performances of England ever since 1990.

Here was where “Three Lions” was truly clever. It didn’t just strike a chord with the new football market, it provided them with an invaluable primer on how to feel about England and history. The song – and I write as a part of that market – is a bluffer’s guide to fandom, an off the shelf attitude to the England team, a way of buying into history and resolving the anxiety of newbiedom – all thanks to the four toxic little words at the song’s heart.

Like all great marketing insights, “thirty years of hurt” is immediately evocative and immensely flexible and extensible. Like many, it’s also meanly prescriptive, telescoping the many possible conflicting feelings about crap performances – like anger, amusement, resignation, or sheer apathy – into one selfish, petulant word. Baddiel, Skinner and Ian Broudie sing “hurt” like they mean it – their performances are so sincere it’s almost mawkish: football fans as sad, big-eyed pups. But however they meant “hurt”, it was also a summary of the entitlement the English media began to show about international football – the shimmering history of the game since 1966 reduced to a barren stretch in which “we” didn’t win anything.

The cavalier treatment of history is characteristic of Sky-era sport – but it resonated more widely. “Three Lions” fit its pop moment as well as its football one, landing at a time when a chunk of Britain’s music talent seemed fixed on play-acting the 60s. “Three Lions” is a superior Britpop song, whatever else it is – too earnest and not as sharp or funny as the genre’s best, but Skinner and Baddiel’s rough voices have a folksy conviction and charm which a lot of minor Britpop bands lacked, and the Lightning Seeds could always sell a sappy tune.

Back in 1966, pop and football had little enough to do with one another. But in nostalgia’s lens the heights of pop creativity and England’s footballing powers had become linked, part of the same golden dream. So in the magical working that was Britpop, the Euro 96 tournament could be a sympathetic ritual replay of 1966 – and the climax of “Three Lions” comes when the singers unite on a line that seems to move beyond even prayer and into spell. “I know that was then – but it could be again.” At that moment the song stops, and it’s as if Baddiel and Skinner (and us, if we want to join in) have their eyes squeezed tight shut, willing time to unravel and the world to rewrite itself around our glorious past.

The song starts up again. The moment passes. Our brave lions (etc) go out on penalties against “the Germans”. The cycle continues.

POSTSCRIPT (A bit of Meta-Business).

In 2008 (42 years of hurt! And counting!) I wrote this: “I occasionally think of Popular as a three-act story: this [The Sex Pistols’ “God Save The Queen”] is the end of Act I, the false start of the second great age of singles, which was also the world that shaped me as a listener.” And this, for what it’s worth, is the end of Act II.

The relationship between the Pistols and this song probably seems rather obscure. It is rather obscure, if only because “Three Lions” is the product of a pop culture where the legends of punk had become part of the mainstream context of everything. “Three Lions” is in no sense a punk record. But the three men who made “Three Lions” were shaped by punk’s consequences, and so was the world it was released into. Broudie was a player on the Liverpool post-punk scene. Baddiel and Skinner were second-generation inheritors of “alternative comedy” and its sometimes conscious application of punky ideas and salesmanship to stand-up. The positioning of “Three Lions” – a more alternative, more authentic football single than previous official FA product – is classic indie ju-jitsu marketing, and as such also inherited from punk. Assume the underdog role and never let it go – even when you’re Number One.

“Three Lions” frames the problem of English football in a way that would become increasingly familiar. Football had lost its way, lost its hunger and passion and cheek, but with those it could go back to the golden age. It was

an alluring story – and it was also the the same way Oasis had framed the problem of English pop. “I know that was then but it could be again”. This was one of the fatal promises of punk, or at least punk as the culture came to remember it – punk as a giant reset button on a stagnant scene. But once you had shown there might be a reset button, the lure of pressing it again became far stronger. Once you admit the possibility of going back to basics, moving forward, and working with what you have, becomes a lot harder. And the alternative – Jules Rimet still gleaming, England still dreaming – grows more and more seductive.

Original source cartechboy writes “As car manufacturers battle over futuristic announcements of when autonomous cars will (allegedly) be sold, they are also starting to more seriously put self-driving technology to the test. Earlier this week several Japanese dignitaries drove — make that rode along — as an autonomous Nissan Leaf prototype completed its first public highway test near Tokyo. The Nissan Leaf electric car successfully negotiated a section of the Sagami Expressway southwest of Tokyo, with a local Governor and Nissan Vice Chairman Toshiyuki Shiga onboard. The test drive reached speeds of 50 mph and took place entirely automatically, though it was carried out with the cooperation of local authorities, who no doubt cleared traffic to make the test a little easier. Nissan has already stated its intent to offer a fully autonomous car for sale by 2020.”

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Saab has chosen this image taken by Mirco Knecht as the winner of its latest Gripen photo competition. The picture, taken during the practice days for the Axalp 2013 event, will now feature in the airframer’s 2014 calendar.