TL;DR: The points gap was too much too small.

I took Judith on a fairly long trip to York and she was using more fuel than normal, the idle was lumpy and – towards the end of the run – she was increasingly popping, backfiring and stalling at idle – but was running OK at higher revs.

As I was staying at TomB engineering we had a full garage of tools and two pairs of hands which made things easier. First off we dropped the fuel tank to replace the split fuel line previously identified. Whilst a good thing to have done it didn’t make a difference.

The key symptoms were pops and backfires causing the engine to stall. Adding some choke seemed to help but there was lots of soot coming out of the exhaust and collecting on the drive under the back of the car.

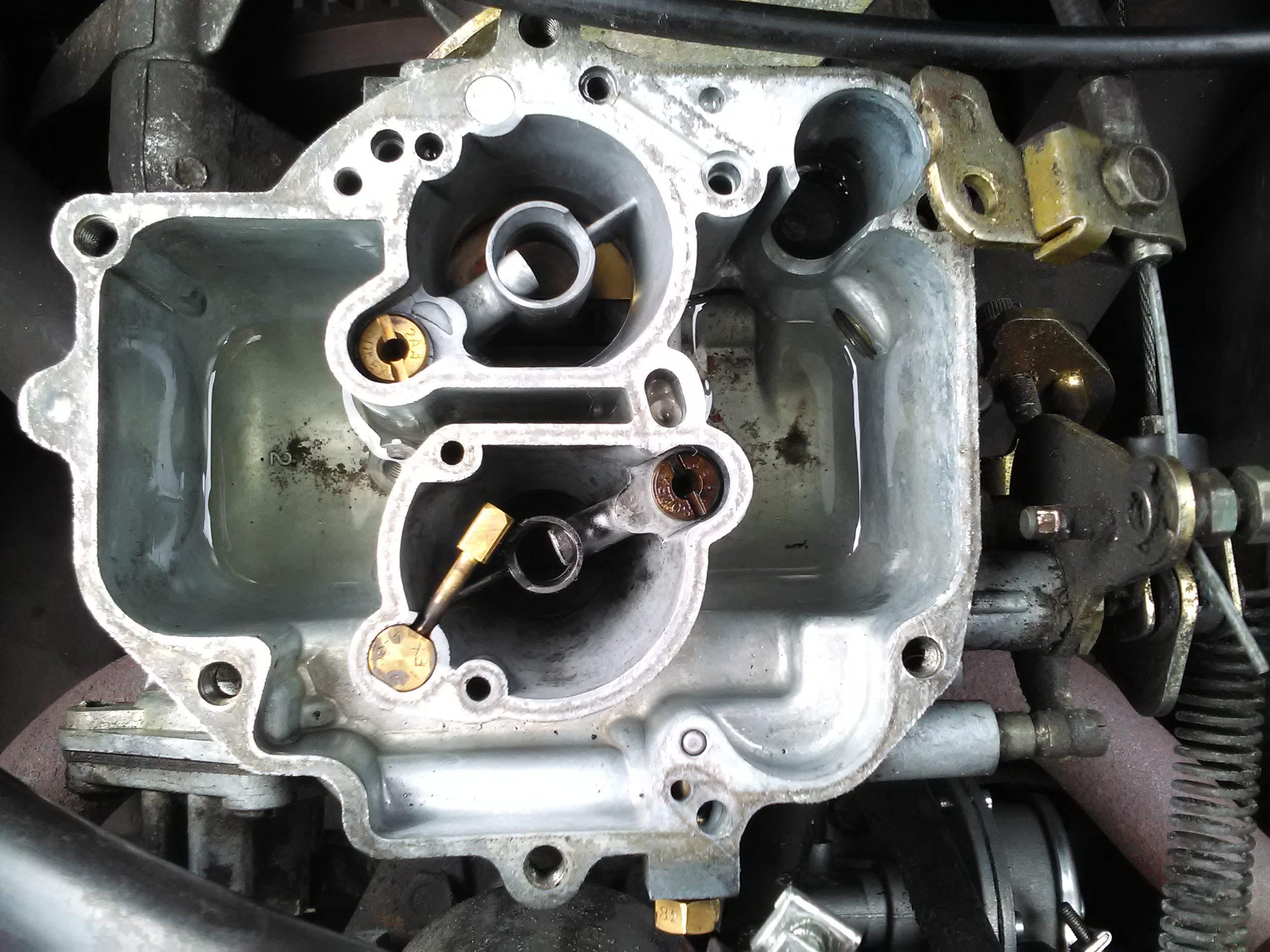

With a rich mixture the first thing to check was the carb but, without dismantling it, it seemed fine – including the idle jet. (With hindsight, the fact it did run a bit better with some choke – which richens the mix – suggests that the mixture wasn’t the issue.)

A short consultation with my Dad and his first suggestion was to check the ignition timing. Whilst she’s not done many miles since it was set, it’s possible something had moved.

As one thing TomB didn’t have was a timing light he set about making one from spare parts (the Megan light cluster finally providing itself something other than a complete pain the derrière) whilst I checked the points gap. The gap is supposed to be 0.4mm but it was down to under 0.1mm – clearly something that needed fixing. Re-setting the gap was accomplished with no difficultly and, when testing the timing, it was spot on indicating that nothing else had moved.

She then fired up on the button and the tickover was spot-on. A short test drive in the last of the afternoon sun confirmed things were back to their best. The run back to Scotland the next day passed off without incident – and used much less fuel!

So what was going on?

The spark is generated when the points open and the LT field in the coil collapses inducing a current in the HT circuit.

When the points are closed (i.e. the follower is on the flats of the cam) the charge builds in the coil. Then when the heel of the cam comes round it opens the points. The gap spacing controls the amount of time the points are closed – this is known as the dwell angle – smaller gap is a longer dwell, with a small gap it’s only the tip of the heel that will open the points. The flip side of the smaller gap is that the points will open later (i.e. only the tip of the heel, not part way up the heel). As the points are opening later in the rotation that has the effect of retarding the timing – and that’s where Judith was sitting.

Normal static timing is eight degrees before top dead centre, the retardation will mean it’s firing (probably) at, or after, after TDC so the mixture is being thinned out and there will likely be incomplete combustion. Given the wasted spark it also means there will be a spark on the exhaust stroke of the opposite cylinder which will be igniting the unburnt fuel – this will be the pops and backfires.

Now to the next bit – the centrifugal timing advance. Combustion basically always takes the same time so as the engine rotates faster the spark needs to fire earlier to ensure the explosion happens at the right time to deliver the power on the down stroke. To accomplish this there are a set of sprung weights between the cam shaft and the timing cam that have the effect of rotating the timing cam relative to the cam shaft thus advancing the timing.

So Judith was running with retarded timing at idle – causing the incomplete combustion (not running rich as we first thought) and the popping and backfires that stalled the engine. However, as the revs built the centrifugal timing advance was cancelling this retardation which explains why she was able to run at high revs – albeit using more fuel to get there as it wasn’t fully burning.